'Un Caso Clinico' BUZZATI (I906-I972)

'In Les Bátisseurs d'Empire the flight from death takes the form of trying to escape upwards. The same image appears in the opposite direction in a remarkable play by Dino Buzzati, the eminent Italian novelist and journalist on the staff of the Corriere della Sera in Milan. This play, first performed by the Piccolo Teatro, Milan, in 1953, and in Paris in an adaptation by Camus in 1955, is Un Caso Clinico. In two parts (thirteen scenes), it shows the death of a middle-aged businessman, Giovanni Corte. Busy, overworked, tyrannized but pampered as the family's breadwinner, whose health must be preserved, he is disturbed by hallucinations of a female voice calling him from the distance and by the spectre of a woman that seems to haunt his house. He is persuaded to consult a famous specialist, and goes to see him at his ultra-modern hospital. Before he knows what has happened, he is an inmate of the hospital, about to be operated on. Everybody reassures him - this hospital is organized in the most efficient modern manner; the people who are not really ill, or merely under observation, are on the top floor, the seventh. Those who are slightly less well are on the sixth; those who are ill, but not really badly, are on the fifth; and so on downwards in a descending order to the first floor, which is the antechamber of death.

In a terrifying sequence of scenes, Buzzati shows his hero's descent. At first he is moved to the sixth floor, merely to make room for someone who needs his private ward more than does. Further down, he still hopes that he is merely going down to be near some specialized medical facilities he needs, and before he has fully realized what has happened, he is so far down that there is no hope of escape. He is buried among the outcasts who have already been given up, the lowest class of human beings - the dying. Corte's mother comes to take him home, but it is too late.

Un Caso Clinico is a remarkable and highly original work, a modern miracle play in the tradition of Everyman. It dramatizes the death of a rich man - his delusion that somehow he is in a special class, exempt from the ravages of illness; his gradual loss of contact with reality; and, above all, the imperceptible manner of his descent and its sudden revelation to him. And in the hospital, with its rigid stratification, Buzzati has found a terrifying image of society itself - an impersonal organization that hustles the individual on his way to death, caring for him, providing services, but at the same time distant, rule-ridden, incomprehensible, and cruel.'

|

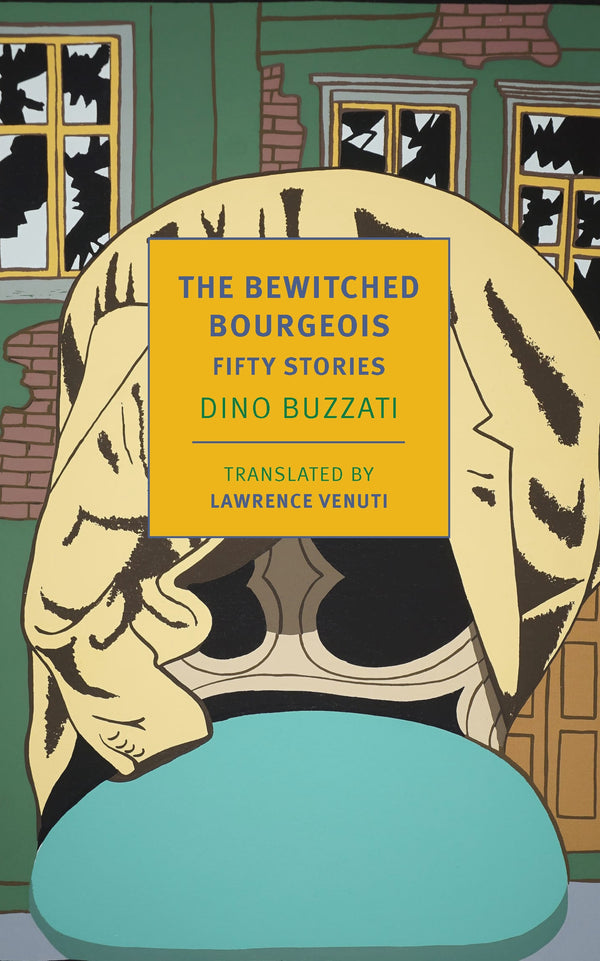

| The Bewitched Bourgeois |

Update: 11th January 2025: c/o John Self. Meet the forgotten maestro of the ultra-short story. Saturday Review, The Times, p.15.

'One of his most widely published stories, Seven Floors, is set in a hospital where they put the "mildest cases" on the seventh floor, and so on in increasing order of sickness down to the first floor, which is occupied by those who are "beyond hope"'.

orcid.org/0000-0002-0192-8965

orcid.org/0000-0002-0192-8965